Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:01

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:01Part Six

When money speaks, the truth remains silent.

Russian proverb.

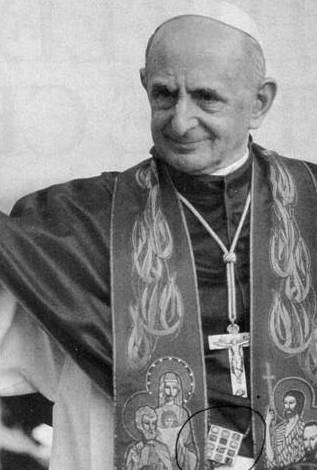

The adventurer Michele Sindona was already at the head of a vast financial empire when his friend Pope Paul VI, in 1969, made use of his services as financial adviser to the Vatican. The Sicilian’s influence on both sides of the Atlantic was sufficient to ensure that he received universal respect; irrespective of personal character. The American ambassador in Rome referred to Sindona as ‘the man of the year’, and Time magazine was later to call him ‘the greatest Italian since Mussolini’.

His connection with the Vatican increased his status, and his business operations, carried out with the dexterity of a spider spinning a web, soon placed him on a near footing with the more political and publicly advertised Rothschilds and Rockefellers. He burrowed into banks and foreign exchange agencies, outwitted partners as well as rivals, and always emerged in a controlling capacity.

He invested money under assumed or other persons’ names, disposing of and diverting funds, always with set purpose, and he pulled strings for the underground activities of the Central Intelligence Agency as well as for more secret bodies, that brought about political repercussions in European centres. All this was done with an air of confidential propriety and by methods that would not have survived the most casual examination, carried out by the most inefficient accountant.

One of his early banking contacts was with Hambro, and from that followed a list that came to include the Privata Italiana, Banca Unione, and the Banco di Messina, a Sicilian bank that he later owned. He held a majority stake in the Franklin National Bank of New York, controlled a network that covered nine banks, and became vice-president of three of them. The real assets of those banks were transferred to tax shelters such as Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Liberia.

Before long he had taken over the Franklin National, with its 104 branches and assets of more than five billion dollars, despite an American law that forbade direct ownership of any bank by groups with other financial interests. But a way round this was found by the then President Nixon, and by Sindona’s friend and share manipulator David Kennedy, a former secretary to the United States treasury and that country’s ambassador to Nato.

At one time it was reckoned that the amount involved in his foreign speculations alone exceeded twenty billion dollars. Apart from the interests already named, two Russian banks and the National Westminster were finger deep in his transactions. He was president of seven Italian companies, and the managing director of several more, with shares in the Paramount Pictures Corporation, Mediterranean Holidays, and the Dominican sugar trade. He had a voice on the board of Libby’s, the Chicago food combine. He bought a steel foundry in Milan.

It was only to be expected that, when estimating such a man, his past and his character counted for less than the jingle in his pocket. New friends, acquaintances, public figures, and distant relatives pressed forward for a sight of the Sindona smile; and among them was a churchman, Monsignor Ameleto Tondini. Through him the financier met Massimo Spada, who managed the affairs of the Vatican bank, or, to give it a more innocuous title, the Institute for Religious Works.

Its main concern was with the handling of Vatican investments, which to some extent came under a body known as the Patrimony of the Apostolic See. That had come into existence, as a financial entity, in 1929, under one of the conditions of the Lateran Treaty concluded with Mussolini.

It had since outgrown the limitations imposed by the Treaty, and had taken on truly international dimensions under a conglomerate of bankers including John Pierpont Morgan of New York, the Paris Rothschilds, and the Hambros Bank of London. Its clerical supervisor was Monsignor (soon to be Cardinal) Sergio Guerri.

Spada, who was the chairman of Lancia, became chairman of a part ecclesiastical, part financial institution, known as the Pius XII Foundation for the Lay Apostleship, a very wealthy concern which was later taken over by Cardinal Villot, who was in many ways a reflection of Paul VI.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:

Sixième partie

Quand l'argent parle, la vérité se tait.

Proverbe russe.

L'aventurier Michele Sindona était déjà à la tête d'un vaste empire financier lorsque son ami le Pape Paul VI, en 1969, avait recours à ses services comme conseiller financier du Vatican. L'influence de la Sicile, des deux côtés de l'Atlantique était suffisante pour assurer qu'il reçut le respect universel, quel que soit sa personnalité. L'ambassadeur américain à Rome voit Sindona comme «l'homme de l'année », et le magazine Time de l'appeler, par la suite, « le plus grand Italien depuis Mussolini. »

Ses liens avec le Vatican ont augmenté son statut et ses activités commerciales, réalisées avec la dextérité d'une araignée tissant une toile, l’ont bientôt placé presque sur le même pied que les Rothschild et les Rockefeller. Il se terra dans les banques et les agences de change, déjoua ses partenaires aussi bien que ses rivaux, et, toujours, émergeas avec la capacité de contrôle la donne.

Il a investi de l'argent sous des noms fictifs ou de d’autres personnes, disposant et détournant des fonds , toujours dans un but précis, et il tira les ficelles des activités clandestines de l'Agence centrale de renseignement (Louis :C.I.A. agence américaine) ainsi que pour beaucoup de services secrets, ce qui eut des répercussions politiques dans des centres européens. Tout cela fait avec un air de confidentialité et selon des méthodes qui n'auraient pas survécu à la plus sommaire et impromptue des vérifications , effectuée par l'expert-comptable le incompétent.

Un de ses contacts bancaires du début était avec Hambro, et fut suivi d'une liste qui est venu à inclure la Privata Italiana, Banca Unione, et la Banco di Messina, une banque sicilienne dont il deviendra propriétaire. Il détenait une participation majoritaire dans la Franklin National Bank, de New York, contrôlait un réseau comprenant neuf banques, et devient vice-président de trois d'entre elles. Les actifs de ces banques ont été transférés dans des abris fiscaux comme la Suisse, le Luxembourg et le Libéria.

A un moment donné, il avait pris le contrôle de la Franklin National avec ses 104 succursales et un actif de plus de cinq milliards de dollars, malgré une loi américaine qui interdisait la propriété directe d'une banque par des groupes ayant d'autres intérêts financiers. Mais un moyen de contourner cela a été trouvé par le président d’alors, le Président Nixon, et par l'ami et manipulateur d’actions de Sindona , David Kennedy, un ancien secrétaire du Trésor des États-Unis et l'Ambassadeur de ce pays à l'OTAN.

A un moment donné, il fut évalué que le montant en cause dans ses spéculations étrangères, à elles seules, totalisaient plus de vingt milliards de dollars. Outre les intérêts déjà mentionnés, deux banques de Russie et la National Westminster étaient trempaient dans ses transactions. Il a été président de sept entreprises italiennes, et le directeur général de plusieurs autres, avec des actions dans la Paramount Pictures Corporation (Louis : grande société de production cinématographique, États-Unis), Mediterranean Holidays (Louis : Vacances dans la Méditerranée ?), et le commerce de la canne à sucre de la République Dominicaine (?). Il avait une voix au conseil d'administration de Libby, le conglomérat alimentaire de Chicago. Il acheta une fonderie d'acier à Milan.

Il est tout à fait normal quand vient le temps d’apprécier un tel homme, son passé et sa personnalité comptent pour moins que l’argent trébuchant qu’il a dans sa poche. De nouveaux amis, des connaissances, des personnalités publiques, et des parents éloignés se pressaient pour voir le sourire de Sindona, et parmi eux était un homme d'Église, Mgr Ameleto Tondini. Par lui, le financier a rencontré Massimo Spada, qui gérait les affaires de la banque du Vatican, ou, pour lui donner un titre plus inoffensif, l'Institut pour les Œuvres Religieuses (Louis : I.O.R.)

Sa principale préoccupation était de gérer les investissements du Vatican, qui d’une certaine mesure, relevaient d'un organisme nommé le Patrimoine du Siège Apostolique. Qui existait, comme une entité financière, depuis 1929, sous l'une des conditions du traité du Latran conclus avec Mussolini.

Depuis, il a dépassé les limites imposées par le traité, et a pris une dimension véritablement internationale en vertu d'un conglomérat de banquiers dont John Pierpont Morgan de New York, les Rothschild de Paris, et la Hambros Bank of London. Son supérieur ecclésiastique était Monseigneur (qui sera bientôt Cardinal) Sergio Guerri.

Spada, qui était le président de Lancia, est devenu président d’uns institution partie ecclésiastique, partie financière, connue comme la Fondation Pie XII pour l'Apostolat Laïc, une entreprise en très grande santé financière, qui a été ensuite reprise par le Cardinal Villot, qui était, à maints égards, un miroir de Paul VI.

A suivre...

Javier- Nombre de messages: 1051

Localisation: Ilici Augusta (Hispania)

Date d'inscription: 26/02/2009

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:08

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:082.

There is always a sinister side to big money dealings, and one of Sindona’s associates, Giorgio Ambrosoli, became increasingly nervous as the carrying out of increasing frauds kept pace with the profits, and with the effects they produced in several European social, economic, and political structures. He expressed his doubts to Sindona, who brushed them aside. But he did not do the same with Ambrosoli. Instead he made him the object of rumour and surrounded him with a network of suspicion. And one more unsolved crime was added to the Italian police register when Ambrosoli was shot dead outside his house by ‘unknown assassins’.

Even before Sindona was concerned with its investment policy, the Vatican, despite its condemnation of money-power in the past, was heavily involved in the capitalist system. It had interests in the Rothschild Bank in France, and in the Chase Manhattan Bank with its fifty-seven branches in forty-four countries; in the Credit Suisse in Zurich and also in London; in the Morgan Bank, and in the Banker Trust. It had large share holdings in General Motors, General Electric, Shell Oil, Gulf Oil, and in Bethlehem Steel.

Vatican representatives figured on the board of Finsider which, with its capital of 195 million lire spread through twenty-four companies, produced ninety per cent of Italian steel, besides controlling two shipping lines and the Alfa Romeo firm. Most of the Italian luxury hotels, including the Rome Hilton, were also among the items that figured in the Vatican share portfolio.

Sindona’s influence at the Vatican, deriving from his earlier friendship with Paul VI, and the recent meetings with Spada, was soon felt in much the same way as it had been in the outer world. He assumed complete control of the Banca Privata. He bought the Feltrinelli publishing house, and the Vatican shared in its income despite the fact that some of its productions included calls to street violence and secret society propaganda. The same quarter gave support to Left-wing Trades Unions, and to the none too healthy work, often on the seamy side of the law, conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency. The same lack of discernment was shown by the fact that one of the firms that helped to swell the Sindona Vatican funds had been making, at least for a time, contraceptive pills.

Other and more direct Vatican commitments were with the Ceramica Pozzi which supplied taps, sanitary equipment, and bidets, and with a chemical group, again with Hambros in the background, that manufactured synthetic fibres for textiles. Vatican representatives appeared on the boards of Italian and Swiss banks, and their influence was increasingly felt in the management of holding companies in many parts of the Western world.

Another ‘shut eye’ operation was when Cardinal Casaroli concluded an agreement with Communist authorities, whereby one of the Vatican companies erected a factory in Budapest.

Almost within hearing distance of the work was another Cardinal, Mindszenty, Archbishop of Hungary who, abandoned by Rome because of his anti-Communist stand, had taken refuge in the American Embassy after the abortive 1956 uprising.

Had it been possible to conduct a genuine inquiry at that time, the names of Vatican officials would have been found figuring in some of President Nixon’s complicated ventures. So much emerges when, by steering a way through a mass of often contradictory manoeuvres, one pin-points the Vatican ownership of the General Immobiliare, one of the world’s largest construction companies which dealt in land speculation, built motorways and the Pan Am offices, to quote but a few of its operations, and also controlled a major part of the Watergate complex in Washington. It was thereby enabled to build, and own, the series of luxury buildings on the banks of the River Potomac that became the headquarters of the Democratic electoral campaign in 1972.

The management of the Generale Immobiliare was in the hands of Count Enrico Galeazzi, the director of an investment and credit company (estimated capital twenty-five billion lire), who could so freely come and go at the Vatican that he was known as the laypope.

The Holy See became a substantial partner in Sindona’s commercial and industrial empire in the spring of 1969 when, in answer to calls from Paul VI, the financier made several visits to the Vatican where the two men met, in the Pope’s study on the third floor, at midnight. (Only, so far as the minor clerics and staff of the Vatican were concerned, and according to the Pope’s appointment book that was duly ‘doctored’ before being entered up, it was not His Holiness who conferred with Sindona but Cardinal Guerri, who in all probability was sleeping at the time.)

Besides wishing to fortify the Vatican’s investment policy, the Pope was concerned with maintaining the Church’s non-liability for Government control, in the shape of tax, of its currency and assets. That exemption, with the Christian Democrats heading a four-party coalition since the end of the Second World War, had never been seriously questioned. But new voices were now being heard. The Vatican was named as the biggest tax-evader in post-war Italy, and there was a growing demand for its arrears to be settled.

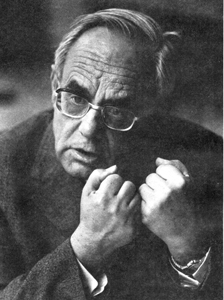

Another member of this sanctified business circle was Paul Marcinkus, one of a Lithuanian family who had emigrated to Chicago. He was in the good books of Monsignor Pasquali Macchi, the Pope’s personal secretary, and had so far not been prominent in any pastoral field. His most practical experience, in the sphere of Church activity had been gained when, due to his standing six feet four in his socks, and his long powerful arms (which earned him the nickname of ‘gorilla’) he supervised the guarding of Paul VI during his travels. Paul made him a Bishop.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:

2.

Il ya toujours un côté sinistre à des transactions de gros sous, et l'un des associés de Sindona, Giorgio Ambrosoli, est devenu de plus en plus nerveux à mesure que les fraudes augmentaient au même rythme que les bénéfices, et avec les effets qu'elles produisaient dans les structure sociales, économiques et politiques dans plusieurs pays d'Europe. Il exprima ses doutes à Sindona, qui les écarta. Mais il ne fit pas de même avec Ambrosoli. Au lieu de cela, il a fait de lui l'objet de rumeurs et l'entoura d’un réseau de suspicion. Et un crime non résolu de plus a été ajouté au registre de la police italienne quand Ambrosoli a été abattu devant son domicile par des « assassins inconnus ».

Même avant que Sindona ne s’occupe de la politique d'investissement, le Vatican, en dépit de sa condamnation du pouvoir de l’argent (money power) dans le passé, a été fortement impliqué dans le système capitaliste. Il avait des intérêts dans la banque Rothschild en France, et dans la Chase Manhattan Bank avec ses cinquante-sept succursales dans quarante-quatre pays, dans le Crédit Suisse à Zurich et aussi à Londres, dans la Banque Morgan Bank, and dans la Banker Trust. Il avait beaucoup d’actions dans General Motors, General Electric, Shell Oil, Gulf Oil, et Bethlehem Steel.

Les représentants du Vatican qui siégeaient sur le conseil d'Finsider qui, avec son capital de 195 millions de lires disséminé dans vingt-quatre compagnies, produisait quatre-vingt dix pour cent de l'acier italien, en plus du contrôle de deux lignes maritimes et de la maison d'Alfa Romeo. La plupart des hôtels de luxe italiens, dont l'hôtel Hilton de Rome, étaient également parmi les items qui figuraient dans le portefeuille d'actions du Vatican.

L’influence de Sindona au Vatican, qui découle de son amitié nouée plus tôt avec Paul VI, et des récentes rencontres avec Spada, s’exerça bientôt sentir, dans une grande partie, de la même manière qu’elle l'avait été avec le monde extérieur. Il a pris le complet contrôle de la Banca Privata. Il a acheté la maison d'édition Feltrinelli, et le Vatican fut une partie de ses revenus, en dépit du fait que certaines de ses productions font appel à de la violence de rue et à de la propagande pour les sociétés secrètes. Le même trimestriel apporte son soutien à à ces syndicats ouvriers de Gauche, et au travail pas trop bon pour la santé, souvent le côté sordide de la loi, dirigés par la Central Intelligence Agency (Louis : C.I.A. ; agence américaine). Le même manque de discernement a été démontré par le fait que l'une des entreprises qui ont contribué à gonfler les fonds du Vatican Sindona avait été , au moins pour un temps, dans les pilules contraceptives.

D'autres engagements financiers et plus directs du Vatican ont été Ceramica Pozzi qui fourni des robinets, des équipements sanitaires, et des bidets, et avec un groupe chimique, toujours avec la Hambros Bank of London, comme bailleur, qui fabrique des fibres synthétiques pour les textiles. Les représentants du Vatican siègent sur les conseils des banques italiennes et suisses, et leur influence se fait de plus en plus sentir dans la gestion des sociétés en holding dans de nombreuses parties du monde occidental.

Une autre opération « avec les yeux fermés » fut lorsque le Cardinal Casaroli conclu un accord avec les autorités communistes, en vertu duquel l'une des sociétés du Vatican érigea une usine à Budapest.

Presque à portée de voix de ces travaux est un autre Cardinal, Mindszenty, archevêque de Hongrie qui, abandonné par Rome à cause de sa position anti-communiste, s'était réfugié à l'ambassade américaine après la révolte avortée de 1956.

S'il avait été possible de mener une véritable enquête à ce moment-là, les noms des responsables du Vatican auraient figurés dans certains des entreprises enchevêtrées du président Nixon. Il y en a tant qui émerge quand, en se frayant un chemin à travers ce fouillis de manœuvres souvent contradictoires, on peut pointer du doigt la General Immobiliare, propriété du Vatican, l'une des plus importantes entreprise de construction du monde en ce qui trait à la spéculation foncière, qui construit des autoroutes et les bureaux de la Pan Am (Louis : société américaine de transport aérien de passagers) , pour ne citer que quelques-uns de ses opérations, et contrôlait également une grande partie de l'immeuble Watergate à Washington. Il est, ainsi, possible de construire, et être propriétaires, de la série de luxueux immeubles de sur les rives de la rivière Potomac qui est devenu le siège de la campagne électorale démocratique en 1972.

La gestion de la Generale Immobiliare était entre les mains du Comte Enrico Galeazzi, directeur d'une société d'investissement et de crédit (capital estimé vingt-cinq milliards de lires), qui pouvaient ainsi aller et venir librement au Vatican et qui était connu comme le pape-laïc (laypope) .

Le Saint-Siège est devenu un partenaire important dans l'empire commercial et industriel de Sindona au printemps de 1969 lorsque, en réponse aux appels lancés par Paul VI, le financier a effectué plusieurs visites au Vatican, où les deux hommes se sont rencontrés, dans le cabinet de travail du Pape au troisième étage , à minuit. (Seulement, en autant que les clercs mineurs et le personnel du Vatican sont concernés, et selon le cahiers des rendez-vous du Pape qui a été dûment «trafiqué» avant d'être noté, ce n'était pas Sa Sainteté, qui s'est entretenu avec Sindona, mais le Cardinal Guerri; qui selon toute probabilité, dormait à cette heure.)

En plus de vouloir renforcer la politique d'investissement du Vatican, le Pape s’occupait de maintien de l'Eglise hors du contrôle du gouvernement, en ce qui a trait aux impôts, de ses actifs. Cette exonération, dont les Chrétiens-Démocrates sont à la tête d'une coalition de quatre partis depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, n'avait jamais été sérieusement remise en question. Mais de nouvelles voix s’élevaient. Le Vatican était nommé comme le plus grand abri fiscal dans l’Italie d’après-guerre en Italie, et il y avait une demande grandissante pour que ses arriérages soient mis en ordre.

Un autre membre de ce cercle d'affaires sanctifié fut Paul Marcinkus, issu d'une famille lituanienne qui avait émigré à Chicago. Il était dans les bonnes grâces de de Mgr Macchi Pasquali, secrétaire personnel du Pape, et n'avait jusqu'à présent pas joué aucun rôle important dans n'importe quel domaine pastoral. Son expérience la plus pratique, dans une activité de l’Église fut, lorsqu’en raison de sa capacité de six pieds quatre sans ses souliers, et de ses longs bras puissants (ce qui lui a valu le surnom de «gorille»), il a supervisé la garde de Paul VI au cours de ses voyages. Paul a fait de lui un Évêque.

A suivre…

"Another member of this sanctified business circle was Paul Marcinkus, one of a Lithuanian family who had emigrated to Chicago. He was in the good books of Monsignor Pasquali Macchi, the Pope’s personal secretary, and had so far not been prominent in any pastoral field. His most practical experience, in the sphere of Church activity had been gained when, due to his standing six feet four in his socks, and his long powerful arms (which earned him the nickname of ‘gorilla’) he supervised the guarding of Paul VI during his travels. Paul made him a Bishop".

traduction approximative a écrit:« Un autre membre de ce cercle d'affaires sanctifié fut Paul Marcinkus, issu d'une famille lituanienne qui avait émigré à Chicago. Il était dans les bonnes grâces de de Mgr Macchi Pasquali, secrétaire personnel du Pape, et n'avait jusqu'à présent pas joué aucun rôle important dans n'importe quel domaine pastoral. Son expérience la plus pratique, dans une activité de l’Église fut, lorsqu’en raison de sa capacité de six pieds quatre sans ses souliers, et de ses longs bras puissants (ce qui lui a valu le surnom de «gorille»), il a supervisé la garde de Paul VI au cours de ses voyages. Paul a fait de lui un Évêque. »

Javier- Nombre de messages: 1051

Localisation: Ilici Augusta (Hispania)

Date d'inscription: 26/02/2009

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:22

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:22As controller of the Vatican Bank, a post that was handed to him by Paul VI, Marcinkus was responsible for more than 10,000 accounts belonging to Religious Orders and to private individuals, including the Pope. The number of the latter’s account, by the way, was 16.16. He handled the Vatican’s secret funds and its gold reserves at Fort Knox, and he transferred a substantial part of the funds, in the hope of making a quick profit, to the Sindona holdings.

He was also President of the Institute for Religious Training, and a director of the Continental Illinois Bank of Nassau. His rise was neither unexpected nor brought about without influence being exerted, for on July 2nd, 1963, Marcinkus followed the example of those many clerics who, in defiance of Canon 2335, had joined a secret society. His code name was Marpa.

Taking advantage of the fact that clerical garb was no longer essential, Marcinkus shouldered his way through the fringes, then into the colourful noisy heart, of Roman society. He was the affluent manager of one of the city’s most influential, privileged, and respected banks. He lounged at bars, joined exclusive clubs that had hitherto been envied and far-off places to him, and showed his animal strength on the links by sending numerous golf balls into oblivion. In time his blatant playboy attitude annoyed the more established Roman community, who turned a cold shoulder. It would seem that he had little more than gangling brawn to recommend him. But there were always plenty of Americans, who were there on business, to take their place, though even they were shocked when the Bishop was said to be involved in fraudulent bankruptcy.

Meanwhile the first warnings, conveyed by hints of danger, were reaching Sindona and the Vatican from many parts of the world. The current call was to transfer money to the United States, as events in Europe pointed to political unrest and economic collapse; and the future of the Franklin Bank, in which Sindona and the Vatican were heavily involved, became highly doubtful following a series of disastrous speculations. There were frantic efforts to persuade more secure banks to buy outright, or at least re-float, the Franklin. Calls went out from Montini to arrange the transfer of Vatican investments to a safer haven.

It was not that Sindona had lost his touch; but world forces, assisted by enemies in the Mafia who envied Sindona’s rise, were proving too much for the maintenance of far-flung ventures like some over which he had presided. Aware that he was standing on shaky ground, Sindona tried to gain the support of the Nixon administration, by offering a million dollars, which perhaps could have materialised only if the deal had been accepted, for the President’s electoral fund. But as Sindona, for obvious reasons, insisted on not being named, and since the acceptance of anonymous gifts for an election was forbidden by law, his offer was declined. It was disappointing for all concerned that it impinged upon one of the few laws that even the elastic Federal system could not openly stretch.

Sindona made a final gesture in the approved style of a Hollywood gangster. He threw a lavish and spectacular evening party at Rome’s foremost hotel (that was probably owned by the Vatican) which was attended by the American ambassador, Cardinal Caprio (who had been in charge of Vatican investments before the arrival of Marcinkus), and the accommodating Cardinal Guerri.

Marcinkus merely came in for a great deal of blame. His operations with Vatican funds, said Monsignor Benelli, one of his critics, had been intolerable. But Marcinkus, who knew too much of what went on behind the scenes at the Vatican, could not be abandoned, and he was given a diplomatic post in the Church.

Sindona had been tipped off, by one of his hirelings who was also employed by the secret service, that a warrant was out for his arrest. But he bluffed and drank his way through the festivities, went off for a time to his luxury villa in Geneva, then took a plane to New York.

There, pending actual charges, he was kept under a form of mild surveillance. But it seems that some of those who were detailed to watch him belonged to the Mafia, and the next the Pope heard of his former adviser was that he had been shot and wounded in a scuffle.

It was easy enough, by delving into his past that was more than ankle-deep in great and petty swindles, and now that he was no longer a power to be reckoned with, to bring him to trial; and an attempted kidnap case, and widespread bribery, were now added to the charges against him. When the obliging Cardinal Guerri heard of this, he seems to have become suddenly convinced, perhaps because his name had figured in talks that clinched the bargaining between Pontiff and financier, that Sindona was a much maligned man. He wanted to go to New York and testify on his behalf.

But the Pope, aware of Guerri’s easy-going nature, and not wanting the extent of his own co-operation with the accused to be dragged out in the witness box, kept Guerri in Rome.

The trial ended, in the autumn of 1980, with Sindona receiving a sentence of twenty-five years’ imprisonment. Few, apart from those members of the public who expressed indignation as the financial antics of Sindona were made known to them for the first time, believe that such a sentence will ever be served. At least one anti-clerical paper suggested that Pope Paul was lucky not to have been put on the stand alongside his banker.

As it was, the Pope was left with two reminders of their partnership. The Church had sustained a heavy financial loss which meant, as the Pope asserted with a quite gratuitous beating of the breast, that the Bride of Christ was face to face with bankruptcy; while there was a new administrative agency for finance that he had founded as a result of Sindona’s help.

At the head of this was Cardinal Vagnozzi, Apostolic Delegate in New York. He was assisted by Cardinal Hoeffner, of Cologne, and Cardinal John Cody of Chicago.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:En tant que contrôleur de la Banque du Vatican, un poste qui lui a été confié par Paul VI, il était responsable de plus de 10.000 comptes appartenant à des Ordres Religieux ainsi qu’à des particuliers, y compris le pape. Le numéro de compte de ce dernier, en passant, était 16.16. Il a géré les fonds secrets du Vatican et ses réserves d'or de Fort Knox, et il a transféré une partie substantielle des fonds, dans l'espoir d’en réaliser un profit rapide, dans les holdings de Sindona.

Il fut également président de l'Institut pour la Formation des Religieux de et un administrateur de la Continental Illinois Bank de Nassau. Son ascension n'est ni inattendue, ni ne se réalisa sans qu’aucune influence ne soit exercée : le 2 Juillet 1963, Marcinkus suivit l'exemple de ces nombreux dignitaires religieux qui, au mépris de Canon 2335, avaient rejoint une société secrète. Son nom de code était Marpa.

Profitant du fait que l'habit ecclésiastique n'était plus indispensable, Marcinkus se fraya un chemin à travers les bordures, puis ensuite dans le coeur bruyant et coloré de la société romaine. Il était l’opulent administrateur de l’une des banques les plus influentes, privilégiées et respectées de la ville. Il flânait dans les bars, joignait les clubs les plus sélects qu’il avait jusqu'alors qu’enviés et qui étaient éloignés de lui, et a montré sa force sur les terrains de golf en envoyant de nombreuses balles aux oubliettes. Avec le temps, son attitude flagrante de Playboy agacé la très réputée communauté de Rome, qui lui révéla un accueil plutôt froid. Il semblerait qu'il avait un peu plus que des gros bras pour le recommander. Mais il y avait toujours beaucoup d'Américains qui étaient là, dans les entreprises, pour prendre leur place, même s’ils ont été bouleversés lorsqu’on disait que l’Évêque était impliqué dans une faillite frauduleuse.

Dans l’intervalle les premiers signaux d’alarme, amenés par des indications de danger, atteignaient Sindona et le Vatican et venaient de beaucoup d’endroits dans le monde. Ce qui se faisait alors était de transférer de l'argent aux États-Unis, comme les événements en Europe avaient provoqué de l'agitation politique et un effondrement économique et l'avenir de la Franklin Bank, dans laquelle Sindona et le Vatican étaient largement impliqués, est devenu très incertaine suite à de désastreuses spéculations. On faisait des efforts désespérés pour tenter de convaincre des banques plus sûres de racheter complètement ou au moins refinancer la Franklin Bank. Des appels venant de Montini pour organiser le transfert des investissements Vatican dans un havre sûr.

Ce n'est pas que Sindona avait perdu sa touche; mais les forces mondiales, aidées par ses ennemis dans la Mafia qui enviaient la monté de Sindona, qui approuvaient bien que trop le maintien de ces lointaines et vastes entreprises qu’il avait présidé. Conscient qu'il était sur un terrain glissant, Sindona essaya d'obtenir le soutien de l'administration Nixon, en offrant un million de dollars, ce qui aurait pu se matérialiser si l'entente avait été acceptée, pour le fonds électoral du Président. Mais comme Sindona, pour des raisons évidentes, a insisté pour ne pas que son nom paraisse nulle part, et depuis que l'acceptation des dons anonymes pour une élection était interdite par la loi, son offre a été refusée. Il est décevant pour tous les intéressés qu'il empiétait sur l'une des rares lois que même l'élastique système Fédéral ne pouvait étirer franchement.

Sindona a fait un dernier geste dans le plus pur style d'un gangster d’Hollywood. Il donna une somptueuse et fabuleuse réception dans l’un des plus spectaculaires hôtels de Rome (probablement détenue par le Vatican), à laquelle ont assisté l'ambassadeur américain, le Cardinal Caprio (qui était en charge des investissements du Vatican avant l'arrivée de Marcinkus), et le compatissant Cardinal Guerri.

Marcinkus est venu pour tout simplement recevoir beaucoup de blâme. Ses opérations avec des fonds du Vatican, dit Monseigneur Benelli, un de ses critiques, étaient intolérables. Mais Marcinkus, qui en savait trop ce qui se passait dans les coulisses du Vatican, ne pouvait pas être abandonné, et on lui donna un poste diplomatique dans l'Eglise.

Sindona avait été averti, par un de ses mercenaires qui était aussi à l’emploi des services secrets, qu'un mandat d'arrêt était émis pour son arrestation. Mais il bluffa et bu durant les festivités, partit pour un temps dans sa villa de luxe à Genève, a ensuite pris un avion pour New York.

Là, dans l'attente des charges réelles que l’on avait contre lui, on a exercé sur lui une surveillance légère. Mais il semble que certains de ceux qui affectés à sa surveillance appartenaient à la mafia, et la prochaine fois que le Pape a entendu parler de son ancien conseiller, c'est pour apprendre qu'il avait été blessé par balle dans une bagarre.

Il était assez facile, en fouillant son passé qu’il avait trempé plus que ses chevilles dans de grandes et de petites escroqueries, et maintenant qu'il n'était plus une puissance avec laquelle il faut compter, de le traduire en justice; et un cas de tentative d'enlèvement , et de corruption généralisée, sont maintenant ajoutés aux accusations portées contre lui. Lorsque le serviable Cardinal Guerri a entendu parler de cela, il semble être devenu subitement convaincu, peut-être parce que son nom avait figuré dans les pourparlers qui ont enclenché les négociations entre le Pontife et le financier, que Sindona était un homme de beaucoup diffamé. Il voulait aller à New York et témoigner en son nom.

Mais le Pape, conscient de la nature facile de Guerri, et ne voulant pas que l'étendue de sa propre coopération avec l'accusé ne soit menée dans le box des témoins, il fit que Guerri reste à Rome.

Le procès se termina à l'automne 1980, et Sindona a reçu une peine de vingt-cinq ans d'emprisonnement. Peu, à l'exception de ceux du public qui ont exprimé leur indignation, lorsque les bouffonneries financière de Sindona ont été portées à leur connaissance pour la première fois, croient qu'une telle sentence ne sera jamais servie. Au moins un journal anti-clérical a suggéré que le Pape Paul a eu de la chance de ne pas avoir été mis sur le stand aux côtés de son banquier.

Comme tel, le Pape fut laissé avec deux faits qui lui ont rappelé leur partenariat. L'Eglise avait subi une lourde perte financière ce qui signifiait, comme le Pape l'a affirmé avec un mea culpa tout à fait injustifié, que l'Epouse du Christ était face à face avec la faillite; tandis qu'une nouvelle agence administrative avait été institué pour les finances et qu'il avait fondé comme un résultat de l’aide de Sindona.

Le Cardinal Vagnozzi, délégué apostolique à New York, était à la tête ce cet organisme. Il était assisté par le Cardinal Hoeffner, de Cologne, et du Cardinal John Cody de Chicago.

A suivre…

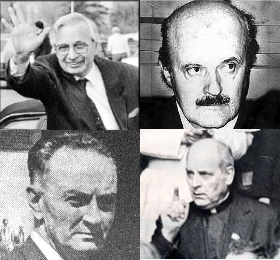

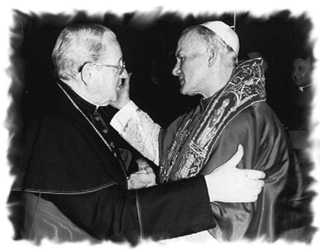

El Cardenal Paul Marcinkus, justificando los negocios del Vaticano montiniano de blanqueo de dinero por la venta de droga y armas, llegó a afirmar: "No se ganan dividendos rezando Aves Marías". A la derecha, Roberto Calvi, "el banquero de Dios", director del Banco Ambrosiano y miembro de la Logia P2, acabó asesinado después de hacer negocios para la secta conciliar de Montini. (Javier)

traduction approximative a écrit:Le Cardinal Paul Marcinkus, pour justifier l'activité du blanchiment d'argent du Vatican montinien par les ventes de drogue et d'armes, est venu dire: « On ne gagne pas des dividendes en récitant des Je vous salue Marie ». Sur la droite, Roberto Calvi, « le banquier de Dieu » directeur de la Banco Ambrosiano et membre de la Loge P2, a été assassiné après avoir fait des affaires pour la secte conciliaire de Montini. (Javier)

Javier- Nombre de messages: 1051

Localisation: Ilici Augusta (Hispania)

Date d'inscription: 26/02/2009

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:29

Javier le Sam 27 Fév - 13:293.

The last named of that trio was soon to make a sensational entry into the news. Cardinal John Patrick Cody, aged seventy-three, the son of a St. Louis fireman, was Archbishop of the largest Roman Catholic diocese in America. He therefore had the handling of many thousands of tax-exempt ecclesiastical funds. And in the autumn of 1981 his congregation was overwhelmed, as only loyal Church members can be, by rumours that soon became facts, to the effect that the United States Attorney’s office in Chicago was looking into Cody’s financial affairs.

A Federal Grand Jury had also asked for the records of a St. Louis investment company, where a certain Mrs. Helen Dolan Wilson had an account, to be examined.

The inquiry, most unusual in the case of a contemporary Cardinal, turned upon what was called the diverting, disposition, or misuse of Church funds amounting to more than £500,000 in English money. It also came to light that the National Conference of Catholic Bishops had lost more than four million dollars in a single year, during which time the Cardinal had been treasurer.

The Mrs. Wilson referred to, of the same age as the Cardinal, was variously referred to as a relation of his by marriage, as his sister, as a niece, while Cody usually spoke of her as his cousin. Her father, more precise judgments claimed, had married the Cardinal’s aunt, while others were sure that no real blood relationship existed between them. The couple concerned said that a brother and sister relationship, begun in their childhood in St. Louis, was their only tie.

‘We were raised together’, explained Mrs. Wilson. Their remaining close friends was therefore a natural development. They travelled together, and for the past twenty-five years she had followed his every move about the diocese. He had become, in the religious sense, her ‘supervisor’, a role that she found beneficial when her marriage, which left her with a son, ended in the divorce court.

It was easy enough for the Cardinal to place her, as manager, in an office connected with the Church in St. Louis. Her appearances there were far from regular but, whether working or not, she nonetheless remained on the Church’s pay-roll. He also helped her son to set up business, in the same town, as an insurance agent, a post that Wilson resigned when, with the Cardinal, he started dealing in ‘real estate’.

Mrs. Wilson retired, after having earned a modest £4,000 a year, but before long she was known to be worth nearly a million dollars, mostly in stocks and bonds. She was also the beneficiary of a hundred thousand dollars insurance policy, taken out on the Cardinal’s life, on which she borrowed.

The inquiries made by the Federal Grand Jury, and publicised by the Chicago Tribune and Sun-Times, brought forth a flood of allegations. The Cardinal had made over most of the missing money to her. Part of it had gone in buying her a house at Boca Raton, in Florida. There had also been a luxury car, expensive clothes and furs, and holiday cash presents.

The Cardinal, though saddened and feeling rejected because of the allegations, was firm in saying that he didn’t need a chance to contradict them. He was ready to forgive all those responsible. Mrs. Wilson was equally firm in saying that she had received no money from the Cardinal. To say that there was anything more than friendship between them was a vicious lie, or even a joke. She strongly resented being scandalised, and being portrayed as a kept woman or (as her fellow-countrymen put it) ‘a tramp’.

Had it not been for the many falls from grace that have overtaken the modern Church, a case like this would scarcely have merited more than a mention. But now it prompts questions. Was it a frame-up, part of the age-long wish to bring the Church into disrepute? Was the Cardinal personally corrupt? Or was he one of the infiltrators who, without any real religious conviction, have been secretly fostered into the Church for the sole purpose of wearing away its moral and traditional fabric?

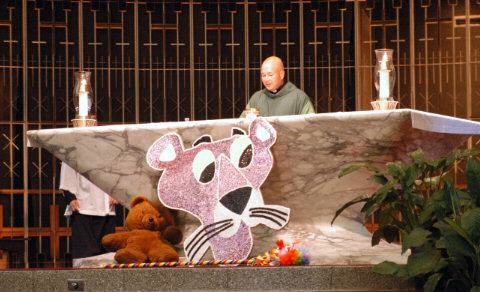

There is, in the light of other strange happenings that have occurred, nothing extravagant in that suggestion; and it would seem to be borne out by a long report in The Chicago Catholic of September 29th, 1978. An Archdiocesan Liturgical Congress was held in order, as one of the jargon-crazed Modernists said, to keep the Church ‘living, moving, changing, growing, becoming new, after some centuries of partial paralysis.’

As part of that process, dance groups frolicked under flashing multi-coloured lights, trumpets blared, people reached and scrambled for gas-filled balloons, and donned buttons that bore the message ‘Jesus loves us’; while a priest, who was looked upon as an expert in the new liturgy, his face whitened like a clown’s, paraded about in a top hat and with a grossly exaggerated potbelly emerging from the cloak he wore.

The background to all this was made up of vestments, banners, and the hotch-potch of a mural, all of which, in the approved style of ‘modern art’, revealed no more than casually applied splashes of paint. The Mass that marked the close of this truly ridiculous Congress (that, as we shall see, was only a faint reflection of what happened elsewhere, and which would never have been dreamt of before the days of ‘Good Pope John’) was presided over by Cardinal Cody.

At another time The Chicago Tribune, in a report describing what was said to be a ‘Gays’ altar’, referred to a concelebration (meaning celebration of the Eucharist by two or more priests) at a church in that city: One hundred and twenty-two priests were present at what passed for Mass, and every one of them was a self-confessed moral pervert.

Neither of these profanities called forth a word of protest from John Patrick, Cardinal Cody.

He died of a heart attack in April, 1982, while this book was in preparation.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:

3.

Le dernier nom de ce trio allait bientôt faire une entrée fracassante dans les nouvelles. Le cardinal John Patrick Cody, âgé de soixante-treize ans, fils d'un pompier de Saint-Louis, fut archevêque du plus grand diocèse catholique en Amérique. Il disposait donc la manipulation d’un fond de plusieurs milliers de dollars, exonéré d'impôt. Et à l'automne 1981, sa congrégation fut bouleversée, comme seuls des membres loyaux de l’Eglise peuvent l’être, par des rumeurs qui allaient bientôt de venir des faits, à l'effet que le bureau du Procureur des États-Unis à Chicago investiguait dans les opérations financières de Cody.

Un Grand Jury Fédéral avait également demandé à ce que les dossiers d'une société d'investissement de St. Louis, où une certaine Mme Helen Dolan Wilson avait un compte, soient examinés.

L'enquête, très rare dans le cas d'un Cardinal de notre temps, se révéla être ce qu’on a appelé la dérivation, la disposition, ou le détournement des fonds de l'Église pour un montant de plus de £ 500.000 en argent anglais. Il a également été mis au jour que la Conférence Nationale des Évêques Catholiques avait perdu plus de quatre millions de dollars en une seule année, période au cours de laquelle le Cardinal en avait été le trésorier.

La Mme Wilson dont on parle , a le même âge que le Cardinal, a été ou une de ses parents par alliance ou comme sa sœur, ou comme sa nièce, tandis que Cody parlait d'elle comme sa cousine. Son père, des arrêts judiciaires plus précis le revendiquent , avait épousé la tante du Cardinal, tandis que d'autres étaient convaincus qu'il n'existe aucun lien de sang réel entre eux. Les deux concernés ont dit que la relation frère et sœur, qui débuta dans leur enfance à Saint-Louis, était leur seul lien.

«Nous avons grandis ensemble », a expliqué Mme Wilson. Leurs proches amis étaient alors un développement naturel. Ils ont voyagé ensemble, et pour les vingt-cinq dernières années, elle a suivi ses moindres gestes dans le diocèse. Il était devenu, au sens religieux, son « superviseur », un rôle qu'elle a apprécié lors de son mariage, qui lui laissa un fils et qui se termina par un divorce devant le juge .

Il fut assez facile pour le Cardinal de la nommer en tant que gestionnaire, dans un bureau reliés avec l'Eglise de Saint-Louis. Ses apparitions n’y étaient pas régulières, mais, qu'elle travaille ou non, elle n'en reste pas moins sur la liste de paie de l'Eglise. Il a aussi aidé son fils à créer sa propre entreprise, dans la même ville, comme agent d'assurance, un poste dont Wilson a démissionné quand, avec le Cardinal, il a commencé à donner dans « l’immobilier ».

Mme Wilson a pris sa retraite, après avoir mérité un modeste 4.000 £ par an, mais avant longtemps, mais avant bien longtemps, elle était connue pour posséder près d'un million de dollars, principalement en actions et obligations. Elle fut également le bénéficiaire d'une police d’assurance-vie de cent mille dollars d'assurance, souscrite sur la vie du Cardinal, sur laquelle elle a emprunté.

Les enquêtes faites par le Grand Jury Fédéral, et rendues publiques dans le Chicago Tribune et le Sun-Times, ont amené une tonne d'allégations. La plupart des fonds manquant lui avaient été transférés par le Cardinal. Une partie de ces fonds manquant avait servi à acheter à Mme Wilson une maison à Boca Raton, en Floride. Il y eut aussi une voiture de luxe, des vêtements onéreux et des fourrures ainsi que des cadeaux de fête en argent comptant.

Le Cardinal, bien qu’attristé et se sentant rejeté à cause de ses allégations, a été ferme en disant qu'il n'avait pas besoin d'une chance pour les contredire. Il était prêt à pardonner à tous les responsables. Mme Wilson a été tout aussi ferme en disant qu'elle n'avait pas reçu d'argent du Cardinal. Dire qu'il n'y avait rien de plus que de l'amitié entre eux était un méchant mensonge, ou même une blague. Elle était fortement irritée, étant scandalisée d’être dépeinte comme une femme entretenue ou (comme le disent ses compatriotes) comme « un clochard ».

Si ça n'avait pas été des nombreuses déchéances de la grâce qui ont secoué l'Église moderne, un cas comme celui-ci aurait à peine mérité plus qu'une mention. Mais maintenant, il soulève des questions. Etait-ce un coup monté, un souhait de longue date de jeter l'Eglise dans le discrédit? Est-ce que le Cardinal était personnellement corrompu? Ou était-il l'un des éléments infiltrés qui, sans réelle conviction religieuse, ont été secrètement nourris dans l'Église dans le seul but de ronger son tissu moral et traditionnel?

Il y a, à la lumière de d’autres événements étranges qui ont eu lieu, rien d'extravagant dans cette suggestion, et elle semble être corroborée par un long rapport dans le The Chicago Catholic du 29 septembre 1978. Un Congrès Liturgique de l'Archidiocèse a eu lieu pour, comme le dit un de ces jargon-insensé moderniste, pour garder l'Église « vivante, mouvante, changeante, en évolution, devenant nouvelle, après quelques siècles d'une partielle paralysie . »

Dans ce cadre , des groupes de danse s'ébattent sous des lumières clignotantes et multicolores, des trompettes, les personnes atteignant et se bousculant pour des ballons gonflés au gaz, et mettant des boutons qui portait le message « Jésus nous aime», tandis qu'un prêtre, qui était regardé comme un expert dans la liturgie nouvelle, le visage blanchi comme un clown, paradant avec un chapeau haut de forme et avec une très exagérée bedaine sortant du manteau qu'il portait.

Tout cela était composé de vêtements, de bannières et d'une fresque méli-mélo, dans un style approuvé d’ « art moderne », et que ne se révélait rien de plus qu’être une toile sur laquelle on avait appliqué, avec désinvolture, des éclaboussures de peinture. La messe qui a marqué la clôture de ce Congrès vraiment ridicule (qui, comme nous le verrons, n'est qu'un pâle reflet de ce qui s'est passé ailleurs, et dont on n'aurait jamais rêvé avant l'époque du «Bon Pape Jean») a été présidée par le cardinal Cody.

Une autre fois, The Chicago Tribune, dans un reportage décrivant ce qui se disait être un « maître-autel gai », destiné à une concélébration (ce qui signifie la célébration de l'Eucharistie par deux ou plusieurs prêtres) dans une église de cette ville: Cent vingt- deux prêtres étaient présents à ce qui a passé pour être la Messe, et chacun d'entre eux était de leur propre aveu un perverti moral.

Aucune de ces profanations ne provoqua un mot de protestation de la part John Patrick, le cardinal Cody.

Il est décédé d'une crise cardiaque en avril 1982, alors que ce livre était en préparation.

A suivre…

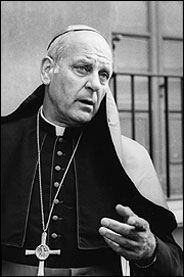

Montini and Cardinal Cody

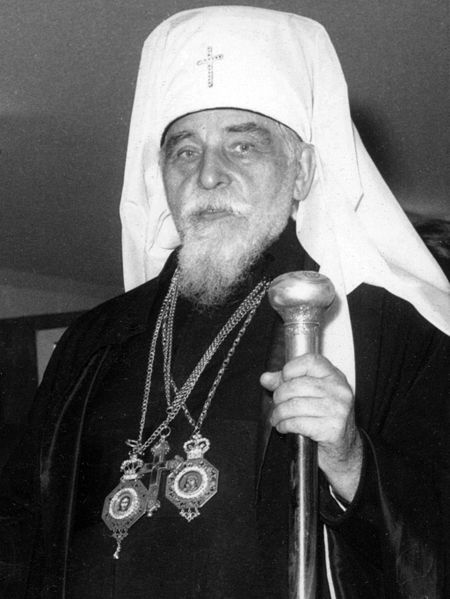

Montini and Cardinal Cody Wojtyla and Cody

Wojtyla and Cody

"An Archdiocesan Liturgical Congress was held in order, as one of the jargon-crazed Modernists said, to keep the Church ‘living, moving, changing, growing, becoming new, after some centuries of partial paralysis.’"

traduction approximative a écrit:« Un Congrès Liturgique de l'Archidiocèse a eu lieu pour, comme le dit un de ces jargon-insensé moderniste, pour garder l'Église ‘vivante, mouvante, changeante, en évolution, devenant nouvelle, après quelques siècles d'une partielle paralysie .’ »

As part of that process, dance groups frolicked under flashing multi-coloured lights, trumpets blared, people reached and scrambled for gas-filled balloons, and donned buttons that bore the message ‘Jesus loves us’; while a priest, who was looked upon as an expert in the new liturgy, his face whitened like a clown’s, paraded about in a top hat and with a grossly exaggerated potbelly emerging from the cloak he wore".

As part of that process, dance groups frolicked under flashing multi-coloured lights, trumpets blared, people reached and scrambled for gas-filled balloons, and donned buttons that bore the message ‘Jesus loves us’; while a priest, who was looked upon as an expert in the new liturgy, his face whitened like a clown’s, paraded about in a top hat and with a grossly exaggerated potbelly emerging from the cloak he wore".traduction approximative a écrit:«Dans ce cadre, des groupes de danse s'ébattent sous des lumières clignotantes et multicolores, des trompettes, les personnes atteignant et se bousculant pour des ballons gonflés au gaz, et mettant des boutons qui portait le message «Jésus nous aime», tandis qu'un prêtre, qui était regardé comme un expert dans la liturgie nouvelle, le visage blanchi comme un clown, paradant avec un chapeau haut de forme et avec une très exagérée bedaine sortant du manteau qu'il portait.»

Javier- Nombre de messages: 1051

Localisation: Ilici Augusta (Hispania)

Date d'inscription: 26/02/2009

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 6 Mar - 13:34

Javier le Sam 6 Mar - 13:34Part Seven

Woe to him who doesn’t know how to wear his mask, be he King or Pope.

Pirandello.

The give-and-take of human relationships poses a more difficult problem than those that are normally accredited to science. For the latter will, in all probability, be solved in time; but when it comes to people, especially those who are no longer among the living, we are faced with questions that, in this our world, are unlikely to be answered.

For instance, it has to be asked why did two prelates, within a few months of each other, both die in circumstances that are not normally connected with any churchman, and, more especially in these cases, highly placed ones?

When a party of Parisians, after having attended a religious festival in the country, returned to the capital late at night on Sunday, May 19th, 1974, some of them noticed that the priest who had been in charge of them looked ill and tired.

He was Jean Daniélou, sixty-nine years old, and a Cardinal; no cut and dried character, but someone difficult to place in the minds of ordinary people who knew very little about him. He had entered a Jesuit novitiate in 1929, and had been ordained nine years later. The author of fourteen books on theology, and the Head of the Theological Faculty at the University of Paris, he was also a member of the Académie Française.

While revealing little, he made certain statements about himself that invited questions; even controversy. ‘I am naturally a pagan, and a Christian only with difficulty’, was one of them, though that, of course, expresses a point a view held by many of his creed who know that little more than a knife edge exists between affirmation and disbelief. He was aware of new elements, that were forming and gathering strength within the Church, and although he judged freely – ‘A kind of fear has spread leading to real intellectual capitulation in the face of carnal excesses’ – the conservatives were no more able to number him among their kind than were the more vocal progressives. He was one of the founders, in 1967, of the Fraternity of Abraham, an interfaith group comprising the three monotheistic religions, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

‘Today is a time when we sin against intelligence.’ Both sides could have claimed that as a dictum. Some accused him, when he appeared to hold back, of being prudish. But always he claimed to be uncommitted. ‘I feel in the depths of my being that I am a free man.’ But freedom, when it is not a political catchword, can no more be tolerated in the world than truth (as the peasant girl Joan of Arc had realised centuries before). And the more Daniélou withdrew from society, and lived quietly at his residence in the Rue Notre-Dame des Champs, without keeping a secretary or running a car, the more he became suspect, or openly disliked.

None of this escaped him, but he tried not to dwell upon it. Had he done so, he owned that he would have been discouraged, a self-evident failure who had not taken advantage of the promise that was made available by his rise in the Church. Later he found, or at least came to believe, that opponents were scheming and plotting against him. There was, indeed, a definite campaign of whispers and hints in the Press that compelled him, though it was more a matter of choice than the force of actual opposition, to maintain a steadily but relatively unimpressive place on the fringe of things.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:

Septième partie

Malheur à celui qui ne sait pas comment porter son masque, qu'il soit roi ou le pape.

Pirandello.

Les accommodements dans les rapports humains posent un problème plus difficile que ceux qui sont normalement accrédités à la science. Pour cette dernière, selon toute probabilité, ils seraient résolus avec le temps, mais quand il s'agit de personnes, notamment celles qui ne sont plus parmi les vivants, nous sommes confrontés à des questions auxquelles, il n’y a que peu de chances qu’il y soit répondu.

Par exemple, il faut se demander pourquoi deux prélats, à quelques mois d'intervalle, tous deux meurent dans des circonstances qui ne sont normalement pas liés à aucun homme d’église, et, plus particulièrement dans ces cas, des haut placés ?

Lorsque les Parisiens, qui après avoir assisté à un festival religieux en région, sont revenus dans la capitale tard dans la nuit, dimanche 19 mai 1974, certains d'entre eux a remarqué que le prêtre qui avait charge d'entre eux avait l'air malade et fatigué.

C’était Jean Daniélou, soixante-neuf ans, un cardinal, pas un caractère tout fait , mais quelqu'un de difficile à situer dans l'esprit des gens ordinaires, qui savaient très peu de choses sur lui. Il était entré au noviciat des Jésuites en 1929, et avait été ordonné neuf ans plus tard. Auteur de quatorze livres de théologie, et le chef de la Faculté de théologie de l'Université de Paris, il fut également membre de l'Académie Française.

Tout en révélant peu, il fit certaines déclarations sur lui-même qui appelaient des questions; voir même la controverse. « Je suis naturellement un païen et un chrétien seulement avec difficulté », fut l’une d'elles, bien que, naturellement, elle exprime un point de vue partagé de ceux qui partageaient ses croyances et qui savent qu’il y a plus qu'une lame de couteau entre l'affirmation et l’incrédulité. Il était au courant des nouveaux éléments, qui se formaient et qui se rassemblaient au sein de l'Eglise, et bien qu'il ait jugé librement. — «Une sorte de peur s'est répandue et qui conduisait à la capitulation intellectuelle réelle face aux excès sensuels (carnal) » – les conservateurs ne sont pas plus en mesure de le compter parmi leurs semblables que ne l'étaient les progressistes, plus bruyants . Il fut l'un des fondateurs, en 1967, de la Fraternité d'Abraham, un groupe interconfessionnel comprenant les trois religions monothéistes, l'islam, le judaïsme et le christianisme.

«Aujourd'hui est un temps où nous péchons contre l'intelligence.» Les deux camps auraient pu y prétendre comme maxime. Certains l'ont accusé, quand il fait marche arrière, d'être prude. Mais toujours, il prétendait ne pas s’être compromis. «J e ressens au plus profond de mon être que je suis un homme libre.» Mais la liberté, quand elle n'est pas un mot d'ordre politique, ne peut pas plus être tolérée dans le monde que la vérité (comme la paysanne Jeanne d'Arc l’avait réalisé plusieurs siècles auparavant). Ainsi, plus Daniélou vit en retrait de la société, et paisiblement à sa résidence de la rue Notre-Dame des Champs, sans avoir de secrétaire ou d'utiliser une voiture, plus il devient suspect ou ouvertement détesté.

Rien de tout cela ne lui échappait, mais il a essayé de ne pas s'y attarder. S'il l'avait fait, il aurait avoué qu'il aurait été découragé, un auto-échec évident qui n'aurait pas profité de la promesse qui devenait possible par sa montée au sein l'Eglise. Plus tard il trouva, ou du moins en est venu à croire, que les opposants intriguaient et complotaient contre lui. Il y avait, en effet, définitivement une campagne de rumeurs et d’insinuations conseils dans la presse qui l'a obligé, quoique c'était plus une question de choix que par la force d'opposition réelle, de maintenir une place régulière mais relativement peu impressionnante sur les lignes de côté (1).

A suivre…

__________________________________________________

(1) Note de Louis : expression employée, ici au Québec, par les commentateurs sportifs qui décrivaient les joutes de football américain et qui signifiait que le joueur restait disponible mais qu’il était un peu en retrait des dimensions du terrain.

Cardinal Daniélou

Cardinal Daniélou

Javier- Nombre de messages: 1051

Localisation: Ilici Augusta (Hispania)

Date d'inscription: 26/02/2009

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 6 Mar - 13:43

Javier le Sam 6 Mar - 13:43So he remained, a problematic figure who arrived home on that Sunday midnight after an exhausting day in the country. But Monday brought no change in his routine. He said Mass, as usual, at eight o’clock, then worked in his office and received a few visitors. He lunched at a restaurant, and afterwards called at the home of a Professor at the Sorbonne.

It appears, for some unexplained reason, that part of his mail went to an address in the Rue Monsieur; for he collected this, was back at his house at three o’clock, then left a quarter of an hour later, after saying that he expected to return at five.

But he did not. For at three forty-eight the police received an urgent message from a Madame Santoni, who occupied an upper floor at number fifty-six in the Rue Dulong, a none too reputable quarter just north of the Boulevard des Batignolles. Her message brought the police rushing to the scene, for it told them that no less a person than a Cardinal was dead on her premises.

He, Daniélou, had called there soon after three-thirty. He had, so someone told her, run up the stairs four at a time, then collapsed at the top, purple in the face, and soon became unconscious. She had torn his clothes apart, and summoned help. But it was impossible to revive him, and the first arrivals had been helplessly looking on when his heart stopped.

In answer to a radio announcement of the Cardinal’s death, the Apostolic Nuncio, with the Jesuit Provincial of France, and Father Coste, Superior of the Jesuits in Paris, arrived at the apartment, together with reporters from the France Soir, and nuns who were called in to deal with the body that was, however, already too rigid to be prepared for the funeral.

Father Coste addressed the reporters. It was essential for them to maintain the utmost discretion, and, having said that, he went on to state that the Cardinal had died in the street, or it may possibly have been on the stairway, after he had fallen in the street.

‘Oh no, it wasn’t’, broke in Madame Santoni. Father Coste objected to her interruption, the other clerics joined in, the police had their say, the reporters asked questions, and at the height of the argument, although no one actually witnessed her going, Madame Santoni disappeared and was seen no more at the inquiry.

Now the lady in question thoroughly deserved the title of Madame. She was well known to the police and to the Press, a twenty-four year old blonde who traded under the name of Mimi, sometimes as hostess at a bar, a go-go girl at an all night cabaret, or as a strip-tease dancer in the Pigalle. She was never on call at her home, which was run as a bawdy-house by her husband. It was then, however, temporarily out of business, as he had been convicted only three days previously for pimping.

Such explanations as the Church chose to offer were vague, and all in line with the general verdict that the Cardinal had burst a blood-vessel, or suffered a heart attack. Cardinal Marty, the Archbishop of Paris, refused a request from Catholics as well as from secular quarters for an inquiry to be held into the Cardinal’s death. After all, he explained, the Cardinal wasn’t there to speak for himself. It may have been an unfortunate afterthought that caused the Archbishop to speak of the Cardinal needing to defend himself. The eulogy was delivered in Rome by Cardinal Garrone who said: ‘God grant us pardon. Our existence cannot fail to include an element of weakness and shadow.’

One may wonder how deep Garrone’s soul-searching may have gone since, although he was known to belong to a secret society, he brazenly sat it out and held on to his red hat. A comment by the orthodox journal La Croix was briefer and more to the point: ‘Whatever the truth is, we Christians well know that each of us is a sinner.’

This sort of happening supplied the Left-wing anti-clerical papers with copy for a week. One such, Le Canard Enchaine, had scored heavily some years before, in a controversy over the ownership of a string of brothels within a few yards of the cathedral in Le Mans. The paper claimed that they were owned by a high dignitary of the Church. His friends and colleagues strongly denied this. But the paper was proved to have been right. Now the same source had no hesitation in saying that the Cardinal had been leading a double life.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:

Il resta donc une figure problématique qui arriva à son domicile ce dimanche soir à minuit, après une journée éreintante dans la région. Mais le lundi, il n’apporte aucun changement dans sa routine. Il dit la messe, comme d'habitude, à huit heures, puis travailla dans son bureau et a reçut un peu de visiteurs. Il déjeuna dans un restaurant, et ensuite appela un professeur de la Sorbonne chez -lui.

Il semble, pour une raison inexpliquée, qu’une partie de son courrier est allée à une adresse de la Rue Monsieur, car il l’a recueilli, était de retour chez lui à trois heures, puis quitte un quart d'heure plus tard, après avoir dit que qu'il envisageait de revenir à cinq heures.

Mais il ne l'a pas fait. Car, à trois heures quarante-huit, la Police Secours a reçu un message urgent d'une madame Santoni, qui occupait un étage supérieur au numéro cinquante-six de la rue Dulong, un quartier qui n’avait pas trop bonne réputation, juste au nord du boulevard des Batignolles. Son message a amené la police à se précipiter sur les lieux, car elle leur a dit que pas moins que la personne d'un cardinal est morte sur les lieux.

Lui, Daniélou, avait appelé, peu après trois heures et demie. Il avait alors, quelqu'un l’avait à la dame, gravi les escaliers quatre par quatre, puis s'est effondré en haut, le visage violacé, et est rapidement devenu inconscient. Elle avait déchiré ses vêtements, et demanda de l'aide. Mais il était impossible de le réanimer, et les premiers arrivants le regardaient, impuissants, quand son cœur s'arrêta.

En réponse à une annonce à la radio de la mort du cardinal, le Nonce apostolique, avec le Provincial des Jésuites de France, et le Père Coste, Supérieur des Jésuites à Paris, est arrivé à l'appartement, avec les reporters de la France Soir, et les religieuses qui avaient été appelées pour s’occuper du corps qui était, toutefois, trop rigide déjà pour être préparé pour les funérailles.

Le Père Coste s’adressa aux journalistes. Il était essentiel pour eux de maintenir la plus grande discrétion, et, ayant dit cela, il poursuivit en déclarant que le cardinal était mort dans la rue, ou peut-être dans l'escalier et qu’après il était tombé dans la rue.

«Oh non, ce n'était pas ça » , interrompit madame Santoni. Le Père Coste s’est objecté opposé à son intrusion, d’autres dignitaires religieux se sont joints, les policiers avaient leur mot à dire, les journalistes posaient des questions, et au plus fort de la discussion, bien que personne de fait assisté à son départ, Mme Santoni disparu et on ne la plus revue de l’enquête.

Maintenant, la dame en question méritait bien le titre de Madame. Elle était bien connue de la police et de la presse, une blonde de vingt-quatre ans, qui travaillait sous le nom de Mimi, parfois comme hôtesse dans un bar, une go-go girl dans un cabaret de nuit, ou comme une effeuilleuse à Pigalle. Elle n'a jamais été sur appel à son domicile, qui était géré comme une maison de débauche par son mari. Il était alors, toutefois, temporairement fermé, car son mari avait été reconnu coupable de proxénétisme trois jours.

Les explications que l'Eglise a choisi d'offrir étaient vagues, et tous en accord avec le verdict général que le cardinal avait eu un vaisseau sanguin qui avait éclaté ou avait subi une crise cardiaque. Le cardinal Marty, archevêque de Paris, a refusé une demande des catholiques ainsi que des quartiers populaires ( secular ) pour qu'une enquête soit tenue sur la mort du cardinal. Après tout, a-t-il expliqué, le cardinal n'était pas là pour parler pour lui-même. Cela a pu être une regrettable pensée après coup qui a incité l’Archevêque de dire parler que le cardinal avait besoin de se défendre lui-même. L'éloge a été prononcé à Rome par le cardinal Garrone qui a dit: «Dieu nous accorde le pardon. Notre existence ne peut manquer d'inclure un élément de faiblesse et d’ombre ».

On peut se demander à quelle profondeur la profondeur est allée l’introspection de l’âme de Garrone, encore qu’il était connu pour appartenir à une société secrète, qu’il est effrontément resté avec et tenait à son chapeau rouge. Un commentaire du journal La Croix a été plus bref et plus au point: «Quelle que soit la vérité, c'est que nous, chrétiens, savons bien que chacun de nous est un pécheur.»

Cette sorte d’événement a fourni aux journaux de gauche anti-cléricaux de la copie pour une semaine. Un de ceux-ci Le Canard Enchaine, avait fortement marqué quelques années auparavant, dans une controverse sur la propriété d'une chaîne de bordels à quelques mètres de la cathédrale du Mans. Le journal faisait valoir qu'elles étaient détenues par un haut dignitaire de l'Église. Ses amis et ses collègues ont vivement nié. Mais il a été prouvé que le journal avait eu raison. Maintenant, la même source dit sans hésiter que le cardinal menait une double vie.

A suivre…

[/url]

[/url]"This sort of happening supplied the Left-wing anti-clerical papers with copy for a week. One such, Le Canard Enchaine, had scored heavily some years before, in a controversy over the ownership of a string of brothels within a few yards of the cathedral in Le Mans. The paper claimed that they were owned by a high dignitary of the Church. His friends and colleagues strongly denied this. But the paper was proved to have been right. Now the same source had no hesitation in saying that the Cardinal had been leading a double life".

traduction approximative a écrit:«Cette sorte d’événement a fourni aux journaux de gauche anti-cléricaux de la copie pour une semaine. Un de ceux-ci Le Canard Enchaîné, avait fortement marqué quelques années auparavant, dans une controverse sur la propriété d'une chaîne de bordels à quelques mètres de la cathédrale du Mans. Le journal faisait valoir qu'elle était détenue par un haut dignitaire de l'Église. Ses amis et ses collègues ont vivement nié. Mais il a été prouvé que le journal avait eu raison. Maintenant, la même source dit sans hésiter que le cardinal menait une double vie. »

Javier- Nombre de messages: 1051

Localisation: Ilici Augusta (Hispania)

Date d'inscription: 26/02/2009

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Re: THE BROKEN CROSS (La croix cassée) par Piers Compton

Javier le Sam 6 Mar - 13:49

Javier le Sam 6 Mar - 13:49He had been under observation for some time, a step that was ordered by no less a person than M. Chirac, the Prime Minister. He and Jacques Foccard, a former Minister of the Interior, both knew perfectly well that the Cardinal had been paying regular visits to Mimi.

That in turn was ridiculed by Daniélou’s supporters; whereupon the paper retorted that there might be more revelations to come. ‘If we were to publish all the details, it would be enough to shut you up for the rest of your natural days.’

The truth of this strange story may lie in one of four possible explanations.

One may have its origin in the effects of the Second Vatican Council. Daniélou was said by some to have regarded that as a positive disaster, and we know that he described the more liberal school of theologians, to which the Council gave rise, as lamentable, miserable, execrable, wretched. Many resented this, especially when he went on to call them ‘assassins of the Faith’. He determined to do what he could to prevent the Faith being secularised and degraded, and this led him to think, since human tempers are just as hot within the Church as they are outside it, that he was in danger. That would account for the somewhat enclosed life he led in Paris.

But he let it be known that he was determined to make a stand, and he drew up a list of those he called traitors to the Church. Some of those whose names were included breathed fire against him, but he publicly announced that he intended to publish the list.

Four days later, according to a theory held by many who are certainly not light-weights, he was murdered by those he would have named. Then, inspired by a kind of macabre humour, those he had called ‘assassins’ had his body taken out and dumped in a brothel. After that, the surprising discovery could easily be arranged.

That is written in full knowledge of how outrageous it must appear to those who regard the Church from a purely parochial level; in happy ignorance of its medieval history that was destined to be repeated, with all the cut-and-thrust and poisoned cups of that period, in a few years’ time, and within the very walls of the Vatican palace.

Or could Daniélou have been, earlier in life, one of those infiltrators whose influence he came to detest? Did he, after being initiated into one of the secret societies opposed to the Church, undergo a change of heart, which caused him to be looked upon as a menace? There is ample evidence that the societies had, and still have, no scruples in dealing with defaulters.

That suggestion is not without substance. For in the Rue Puteaux, Paris, there is an ancient church, the crypt of which serves as the Grand Temple of the Grand Lodge of France. Some three years before Daniélou’s death the Auxiliary Bishop of Paris, Daniel Pézeril, had there been received into the Lodge, after he had issued a communiqué to justify his action. In it he said: ‘It is not the Church which has changed. On the contrary, Masonry has evolved.’ It was Monsignor Pézeril who was asked, by Pope Paul, to seek a way of bridging the gap between the Church and the societies.

Cardinal Daniélou had been a not infrequent visitor to the crypt, where he was seen in consultation with one of the Lodge Masters who had been honoured with the title of Grand Secretary of the Obedience. It must therefore be asked, does the answer to the mystery lie with those with whom Daniélou had conferred in the crypt?

But the story circulated by the satirical papers was the most shrill and insistent, and the most commonly known. They claimed that it had been obvious, to those who had been in Madame Mimi’s apartment before the police arrived, that Daniélou’s body had been hurriedly dressed. And if he had not been one of her clients, why had he gone there with three thousand francs that were found in his pocket-book? The purveyors of such scandal concluded that the Cardinal had died in a state of ecstasy, if not of grace.

Yet another version brings the story more up to date, with a trial that has now (the time is November, 1981) passed through its opening stage in Paris.

On Christmas Eve, 1976, Prince Jean de Broglie was shot dead by a gunman as he left a friend’s house. The necessary inquiries brought a far reaching web of fraud, complicity, and blackmail into the open, involving the former President Giscard d’Estaing and a friend of his, Prince Michel Poniatowski.

The latter had recently ousted and taken the place of Jacques Foccard as Minister of the Interior, and Foccard was now using a woman, who was known also to Giscard, to get money from the Prince. Foccard has already been mentioned in connection with the Daniélou case.

Since the known operation is obviously part of a vast cover-up, it is no more possible, than it is necessary here, to unravel the details, which leave all those concerned in a very murky light. But it is claimed that they account for Daniélou’s being in the brothel, and for the three thousand francs that were found on his person. They were one of the instalments that he had been paying, for the past three months, on behalf of someone, referred to as a friend of his, who was being blackmailed.

A most disarming finale to all this came in the form of a line or two in an English religious weekly, the Catholic Herald, which briefly announced that Cardinal Daniélou had died in Paris.

A SUIVRE...

traduction approximative a écrit:Il avait été sous observation pendant un certain temps, une mesure qui était ordonnée par pas moins que la personne de M. Chirac, le Premier Ministre. Lui et Jacques Foccard, ancien ministre de l'Intérieur, tous les deux savaient parfaitement bien que le cardinal rendait visite régulièrement à Mimi.

Ce qui en soit a été tourné en ridicule par les partisans de Daniélou; ce sur quoi le journal rétorqua qu'il pourrait y avoir plus de révélations à venir. « Si nous devions publier tous les détails, ce serait assez pour vous faire taire pour le restant de vos jours normaux de votre vie ».

La vérité de cette histoire étrange peut se situer dans l'une de quatre explications possibles.

Elle peut avoir son origine dans les effets du concile Vatican II. Certains on dit de Daniélou l’avait considéré comme une catastrophe formelle (positive), et nous savons qu'il décrit l'école la plus libérale des théologiens, dans laquelle le Conseil a donné, de lamentable, de misérable, d’exécrable, de pitoyable. Beaucoup ont été offensé de cela, surtout quand il se mit à les appeler «assassins de la Foi». Il se décida à faire ce qu'il pouvait pour empêcher la foi d’être sécularisé et avilie, ce qui l'a amené à penser que, étant donné que le tempérament de l'homme est tout aussi chaud au sein de l'Eglise comme en dehors, il était en danger. Cela compte pour expliquer la vie un peu clôturée qu’il mena à Paris.

Mais il a fait savoir qu'il était déterminé à prendre position, et il a dressé une liste de ceux qu'il appelait traîtres à l'Église. Certains de ceux dont les noms y étaient écrits, avaient le feu contre lui, mais il annonça publiquement annoncé qu'il avait l'intention de publier la liste.

Quatre jours plus tard, selon une théorie soutenue par de nombreuses personnes qui étaient certes de grande importance, il fut assassiné par ceux qu'il aurait nommés. Puis, inspirée par une sorte d'humour macabre, ceux qu'il a appelés « assassins » ont pris son corps et l’ont jeté dans un bordel. Après cela, la surprenante découverte pourrait facilement être organisée.